Workers Comp is transacted at the state level, subject to state regulation. Most states are ‘competitive rate’ states, which is where LCs and LCMs come into play. A couple of states, such as FL and NJ, are set rate states where the state sets the rate for a given class of business. Not to be confused with monopolistic states like OH or WA, none of which we’re talking about here. What we are talking about is quite simple – the factors used to arrive at WC policy rates and how it applies to sales.

Loss Cost

A Loss Cost is a numerical factor representing the actual or expected cost to an insurer of indemnity payment and allocated loss adjustment expenses (ALAE), and is specific to the class of employment (Class Code) within a given state.

So while the LC can vary quite a bit from state to state, it’s the same for all businesses of a given class within a state. In terms of math it is fixed, a constant.

Loss Cost Multiplier

The LCM is a factor that allows the carrier to adjust this base rate to account for their own expense provisions outside of claim payments and ALAE. Just like the LC, it is typically adjusted or at least reviewed annually.

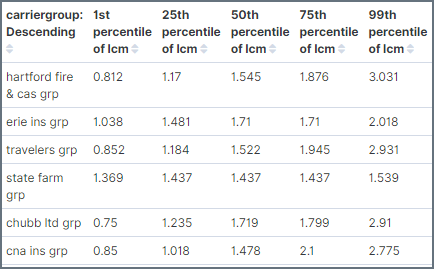

This is the variable. It is specific to the carrier and the state they have filed it in. It is important to note that a carrier group (i.e. Travelers) will have a number of carriers (underwriting co’s), each with their own LCM.

This is where being able to reference state-level active carriers’ LCMs becomes helpful, as shown here in the Class Report, and why they are displayed in the carrier history section.

the Equation

The equation for the policy Rate in these competitive states is: LC x LCM = Rate (a bit underwhelming isn’t it). This is done for each classification listed on a policy.

The equation for Standard Premium = (Payroll/100) x Rate – done for each classification.

So what does it mean?

We know that rates drive premium. Every other WC policy cost factor is based off a percentage of the premium generated by those simple equations. We know that the LC is fixed, as is payroll.

So if we know the incumbent’s LCM capability, and our carrier’s are more competitive (i.e. have lower filings) we have quite a valid reason to check out the situation, and a compelling reason for the prospect to hear you out, especially if the LCM has been trending up over time. This is assuming your carriers want the type of risk you’re looking at, of course. And if you haven’t heard it yet, price isn’t everything. But unless your competition is an incompetent drunk, it is likely a deciding factor.

Other Considerations

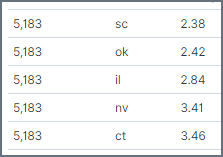

Some states allow for class specific LCM filings. In this case a carrier will file an LCM that applies to the vast majority, and a handful of codes that they can use this ‘sub’ filing on, which is usually much more aggressive than their standard. Others can file tiers at the carrier level (not group). So Carrier A has a preferred, standard and sub-standard tier. In each of these cases we display the standard filing. Known states include VT, NH, NV and CT.

Some states, such as IL, also file a Rate for the voluntary (and assigned risk) market. In these states carriers have the discretion to choose which rating option to use. You can use the Class Lookup resource to see if your state has filed rates available.

Other states use what is called a Rate Relativity. In this scenario the state’s rating bureau establishes relativities for the classes, which is the basis for a policy rate. The carriers file a Deviation which is applied to the Rate Relativity similar to how a LCM is applied to a LC, but from what we’ve seen is more akin to how scheduled credit or debit is applied. Just to keep it confusing, TX lets carriers choose between the LCM or Rate Relativity method.